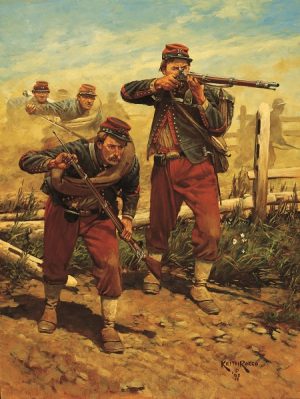

54th Massachusetts Infantry at Fort Wagner

Description

200 signed and numbered prints

By midsummer of 1863, Union forces were ready to make an assault on one of the main defenses of Charleston Harbor. Fort Wagner, a double-bastioned fortification built of sand and reinforced with palmetto revetments, sat on Morris Island, at the southern edge of the harbor. Commanded by Brigadier General William A. Taliaferro, the garrison consisted of a force of 1,700 men and a number of 32-pounder guns.

A direct frontal assault on 11 July, made by seven Federal regiments, failed. In the succeeding week, the Union commander, Major General Quincy A. Gillmore, designed a plan for a sustained naval bombardment followed by a night attack. The bombardment began at noon on 17 July; 9,000 shells were hurled at the fort.

The honor of leading the assault fell to the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a regiment of black soldiers led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, son of an influential Massachusetts abolitionist. Included among its rolls were two sons of Frederick Douglass, a former slave and leading activist for the cause of abolition. Shaw eagerly insisted on the opportunity “to give the black troops a chance to show what stuff they are made of.” The 54th Massachusetts had behaved creditably in combat a few days previously. But at Fort Wagner the regiment would prove the worthiness of black soldiers to a nation filled with doubters and skeptics.

The 54th formed in two ranks behind the shelter of sand hills and prepared to advance along the narrow stretch of beach, the only viable approach. About 6:30 P.M., Colonel Shaw took his place at the head of the line, mounted on his horse. Brigadier General George C. Strong was riding with Shaw. “Take that battery,” he ordered and informed the men that the whole world was waiting for the result of their assault. “I know you will fight for the honor of the State…Don’t fire a musket on the way up, but go in and bayonet them at their guns.” The six hundred men of the 54th waited among the dunes with muskets loaded by not capped, and bayonets fixed.

At last the word came to advance. Colonel Shaw had vowed to “take the fort or die there.” He paused to hand over his personal effects to a friend before giving the word to move forward. The regiment advanced in the darkness as shells from the surrounding islands began to fall among them. Suddenly the fort erupted with light as its guns opened. George E. Stephens, one of the surviving members of the regiment, recalled that “jets of flame darted forth from every corner and embrasure.”

The advance of the 54th Massachusetts stalled at the water-filled moat. Men scrambled to cross, making their way over the bodies of fallen comrades who served as stepping-stones. Upon reaching the ramparts of the fort, casualties mounted; dead and wounded soldiers fell from the wall and into the ditch.

Shaw responded to the desperate situation by raising his sword and ordering the charge. “I saw him…just for an instant, as he sprang into the ditch; his broken and shattered regiment were following him,” wrote a witness. The colonel leapt upon the ramparts; riddled with bullets he fell forward into the fort. In the fury of their assault the men of the 54th gained the parapet and fought the defenders hand to hand. Supporting units were coming up to the fort to join in the attack but too late. Most of the officers of the 54th were killed or wounded. Dozens of men surrendered, only to be bayoneted by the enraged defenders. When the fighting ceased, the 54th Massachusetts counted 272 casualties out of the 600 men and 23 officers who had gone into the flight.

Additional information

| Medium | |

|---|---|

| Size | 24" x 20" |

| Type |